In April 2014 the ACT Government enacted new legal thresholds for serious drug offences. To read about the changes please see: http://www.justice.act.gov.au/page/view/3660/title/criminal-code-controlled-drugs-legislation

Public release of DPMP Monograph 22 was delayed until after enactment of the new laws.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In Australia one of the key measures for distinguishing drug users from traffickers and for determining the seriousness of drug trafficking offences is the quantity of drug involved. Legislative thresholds define the quantity of drug necessary for an offence of trafficking or an offence of minor, mid or high end trafficking, with three thresholds defined in most jurisdictions. The threshold is never the sole factor considered in sentencing drug offenders. But the quantity threshold is arguably the most important factor affecting the sentencing of drug offenders (Model Criminal Code Officers Committee, 1998).

To date there has been surprisingly little use of research to inform decisions on how threshold quantities should be set or what threshold quantities should be used. This is a noted absence since there is considerable variability in the threshold systems across Australia. Moreover, while with good design thresholds can increase the likelihood that sanctions will reflect the offence committed, increase public confidence in sentencing and increase the potential to deter current and would-be offenders, poorly designed quantitative thresholds may do the reverse. Most importantly they may inadvertently increase the risks of disproportionate sanctioning, such as erroneously convicting and imprisoning drug users as drug traffickers or giving overly lenient sanctions to serious drug traffickers. Either consequence could be potentially damaging to the accused and the community.

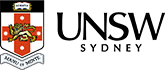

This report outlines a new approach to informing the design of drug trafficking thresholds using evidence on Australian drug markets, drug trafficking and the impacts of drug use/trafficking on the community. It provides expert advice to the ACT Department of Justice and Community Safety on the drug trafficking thresholds specified in Schedule 1 of the ACT Criminal Code Regulation 2005 as they apply to the five most commonly used illicit drugs (heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, MDMA and cannabis). The current threshold quantities, specified in terms of pure drug or active principle, are listed in Table A (Criminal Code Regulation 2005, ACT).

The purpose of this work is:

-

To evaluate current ACT drug trafficking thresholds for trafficable, commercial and large commercial offences; and

-

To evaluate proposed ACT drug trafficking thresholds (under the Model Criminal Code) for trafficable, commercial and large commercial offences; and

-

If necessary, to put forward metrics to assist in the determination of appropriate threshold quantities: how and what threshold quantities should be set.

This report puts forward five evidence-informed metrics through which to evaluate current and potential drug trafficking threshold design. It examines whether the existing ACT thresholds as they apply to heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, MDMA and cannabis:

-

Provide reasonable grounds to assume that all who exceed the trafficable threshold quantities constitute drug traffickers. Do they enable the ACT judiciary to filter out drug users, and minimise the chance that users get charged/sentenced as traffickers for possession for personal use alone? and

-

Are proportional to the potential seriousness of the drug trafficking offence. Do the thresholds enable the ACT judiciary to determine the level of criminality of the alleged trafficker, taking into account traders in different controlled drugs?

Metrics of the likelihood that a drug user will exceed the trafficable threshold for possession for personal use alone included:

-

Metric 1: User patterns of consumption i.e. quantity of drugs that a user is likely to possess for a single session of personal use.

-

Metric 2: User patterns of purchasing i.e. quantity of drugs that a user is likely to possess following a single purchase.

Metrics of the relative seriousness of a drug trafficking offence included:

-

Metric 3: Retail value i.e. amount of revenue that could be made by traffickers of a particular drug.

-

Metric 4: Harm to individuals and society i.e. amount of harm that could result to ACT drug users and the community from trafficking in a particular drug.

-

Metric 5: Social cost i.e. annual cost of healthcare and criminality from each gram of drug that is trafficked in the ACT.

Publicly available data was used for each metric, including retail price and purity from the Illicit Drug Data Report (IDDR) and user patterns of use and purchasing from the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) and the Ecstasy and related Drug Reporting System (EDRS). Indicators of harm to individuals and society were derived from Nutt et al. (2010) and social costs were derived from Moore (2007).

Do the current trafficable threshold quantities provide reasonable grounds to assume that all who exceed the trafficable threshold quantities constitute drug traffickers?

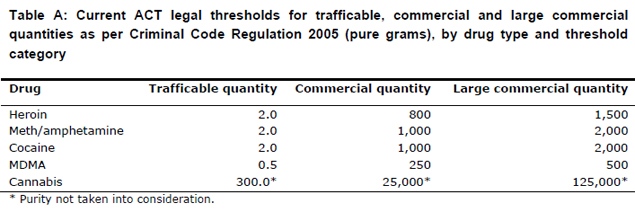

Metric 1 (user patterns of consumption) showed that regular users of heroin, methamphetamine and cannabis consume much less than the current threshold quantity for each drug. This holds regardless of whether they are undertaking a typical or heavy session. But when undertaking a heavy session, users of MDMA may consume more than twice the current trafficable threshold quantity (8.7 grams versus the trafficable threshold set at approximately 3.3 mixed grams).

Metric 2 (user purchasing patterns) indicated that most users purchase less than the current trafficable threshold quantities. Nevertheless, individuals who purchase large quantities of cocaine and MDMA are at risk of exceeding the current thresholds for these drugs. For example, users of cocaine reported purchasing up to 7.5 grams of cocaine in a single buy, yet the trafficable threshold is set at approximately 3.3 mixed grams.

Both metrics suggest that the current trafficable threshold quantities place users of MDMA (and to a lesser extent cocaine) at risk of exceeding the trafficable threshold for an offence involving possession for personal use alone. This increases the likelihood that users will be inadvertently charged and sanctioned for an offence of drug trafficking.

Are the current thresholds (trafficable, commercial and large commercial) proportional to the relative seriousness of a drug trafficking offence?

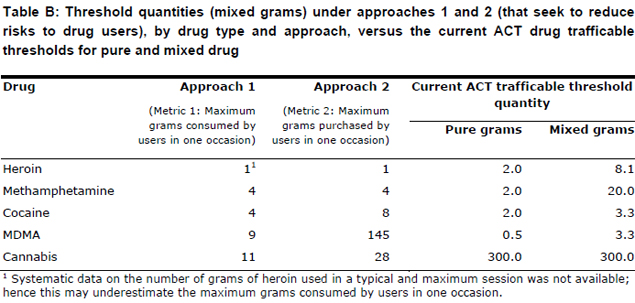

Metric 3 (retail value) showed that the potential retail value for a trafficable quantity of MDMA and cocaine is much lower than the potential retail value of a trafficable quantity of heroin, methamphetamine or cannabis. Indeed, a trafficable quantity of MDMA and cocaine was worth only $223-338 and $814-1,465 respectively. In contrast, a trafficable quantity of methamphetamine affords much greater potential for revenue ($7,000-10,000).

Metric 4 (harm to individuals and society) showed that the potential attributable harm for a trafficable quantity of ‘drugs’ differed greatly across drug types, with the current ACT trafficable quantity of cannabis capable of causing up to 200 times more harm than the trafficable quantity of MDMA.

Assessed against Metric 5 (social cost) the potential social cost from a trafficable threshold quantity is low for cocaine (costing less than $1,758), somewhat higher for cannabis, but very high for heroin and methamphetamine (costing a minimum of $33,064 and $34,200 respectively).

This demonstrates that regardless of which metric is adopted the current legal thresholds are not proportional to the seriousness of drug trafficking offences, and instead vary markedly based on the particular drug that a defendant is found in possession of. This increases risks that some serious traffickers will escape with less serious sanction and some minor traffickers will receive disproportionately harsh sanction. Threshold quantities for commercial and large commercial thresholds are also disproportionate to the potential seriousness of drug trafficking offences, but in their current form, the trafficable threshold is the least justifiable or equitable.

A further challenge with the current thresholds as specified in the Criminal Code Regulation 2005 (ACT) has been the use of a purity-based system. This is problematic as:

-

The ACT currently assesses purity for some drugs, not others.

-

The system is not transparent to buyers or sellers.

-

The system adds to the time and cost of prosecuting serious drug offenders.

-

The system is very subject to fluctuations in purity, increasing the likelihood that responses to drug traffickers will vary across time periods.

In its current design the law thus conflicts with the intended purposes of drug trafficking thresholds: increasing the proportionality and fairness of legal responses. The proposed thresholds under the Model Criminal Code for serious drug offences are equally if not more problematic: if adopted they would increase the risks that users get charged as traffickers.

Towards a more rational response

This report puts forward a methodology to inform the debate about trafficable threshold quantities that could enable more proportional and evidence-informed responses (with commercial and large commercial thresholds to be devised based on the base trafficable threshold). The general principles for a more rational system of thresholds quantities include increasing the proportionality and potential fairness of the law, enshrining principles of harm minimisation (including reducing the potential harm from thresholds themselves) and increasing certainty for offenders, police and prosecutors over what constitutes a low, mid and high-level drug trafficking offence.

Seven potential sets of trafficable threshold quantities for heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, MDMA and cannabis have been put forward. Under all proposed approaches mixed drug have been adopted (not pure drug).

Approaches 1 and 2 seek to minimise the chance that users will exceed the trafficable thresholds for possession for personal use alone (see Table B). Threshold quantities for approach 1 are based on evidence of the maximum quantity that a user is likely to consume (Metric 1). In approach 2 threshold quantities are based on the maximum quantity that a user is likely to purchase (Metric 2). While these thresholds may reduce risks to users, there remains a clear divergence between these, which reflects in part weaker data on Metric 2. A second clear drawback with either approach is that thresholds would remain disproportionate across traffickers in different controlled drugs.

Approaches 3 to 7 seek to both reduce potential risk to users of an unjustified charge of trafficking and increase proportionality across traders, so that regardless of the drug, legal thresholds enable more severe traffickers to be readily distinguished and sanctioned. Accordingly, they take into account both knowledge of user patterns (Metric 1) and the severity of drug trafficking offences, across traders in different controlled drugs (Metrics 3-5). Each proposal is based on a single or combination of metrics of the seriousness of a drug trafficking offence (and hence represent different ways of valuing the seriousness of drug trafficking). For example, under approach 3 threshold quantities are proportionate to the potential retail value for each drug type. In contrast, under approach 7 threshold quantities are proportionate to the potential retail value and harm and social cost for each drug type (an option that would balance the potential revenue that could be garnered by drug traffickers with the harm and economic burden that might ensue on the community). In spite of quite different ways of valuing the impacts of drug trafficking, there remain some very clear synergies across approaches 3-7, most notably that to reduce risks to users and attain more proportionality across traffickers, threshold quantities for MDMA and cocaine ought be higher, and threshold quantities for heroin and methamphetamine ought be lower than in the status quo.

By necessity, designing an alternate set of drug trafficking threshold quantities requires considerations of multiple factors: the evidence-base, value decisions, technical and legislative feasibility and so on. This report considers only the evidence-base. Nevertheless, given the critical role that drug trafficking thresholds play in the sentencing of drug offenders, and demonstrated presence of disproportionate and potential for harmful responses, inserting more rationality into legislative thresholds would be a valuable step. It would also put the ACT at the forefront of developing rational, proportionate sanctioning of serious drug offenders.